Sony NP-FZ100 Batteries at −20 °C: What Actually Happens in the Field

The Sony NP-FZ100 is one of the better mirrorless batteries I’ve used in cold conditions—but let’s be honest: at around −20 °C, physics always wins.

You will see a noticeable drop in usable capacity once both the battery and the camera body are fully chilled. What matters far more than any spec sheet is how you manage warmth, shooting rhythm, and power-hungry habits in the field.

Setting Expectations

Sony rates lithium-ion packs like the NP-FZ100 for operation roughly between 0 °C and 40–45 °C, and performance falls off rapidly once you head well below freezing. In truly cold conditions, losing half—or more—of your normal runtime is common. If you go out at −20 °C, assuming room-temperature performance, frustration is almost guaranteed.

One Warm Battery, Warm Camera (At First)

When both the camera and battery start warm, the pattern is fairly consistent:

For the first 10–15 minutes, things often feel “normal.”

After that, the percentage begins to descend faster than expected.

Long pauses, menu use, and heavy LCD chimping accelerate that decline as the battery cools between bursts.

Once the entire body is at ambient temperature, the remaining percentage on the display is more of a rough estimate than a promise—abrupt shutdowns can occur even when the meter still shows some charge.

Cold Camera, Warm Battery

Dropping a warm NP-FZ100 into a camera that has been sitting at −20 °C is a very different experience. The battery is immediately surrounded by a cold magnesium body, cold electronics, and a chilled display, so it cools rapidly and becomes less able to deliver current efficiently. As a result, the apparent capacity drops much faster than when both the camera and the battery are warm—the pack is effectively placed in a small, well-insulated freezer.

This is where cycling batteries become critical. A pack that seems “dead” in the cold will often deliver a surprising number of extra frames once it warms back up in an inside pocket. In practice, that means planning your shooting in bursts: make images while the battery is warm, then let it recover while another one takes its place.

Two Batteries in a Vertical Grip

Running two NP-FZ100 batteries in a vertical grip changes the equation, mostly in your favour. Drawing from two cells shares the load, reducing the instantaneous current each one must supply and helping them cope with the cold more gracefully.

If both packs begin warm, the combination of extra capacity and shared load can feel close to “normal” for a meaningful stretch of time, and you’re less likely to hit a sudden shutdown in the middle of a good moment. Once both packs and the grip fully chill, the same physics still apply: the curve is gentler, but it’s still heading downhill.

Why Using the EVF Helps

On cameras like the Sony α1 II and Sony α9 III, both of which use the NP-FZ100 battery, the EVF typically draws less power than the rear LCD in real-world use. The EVF is physically smaller and doesn’t ramp up brightness as aggressively as the larger LCD, which makes it a more efficient way to compose and review shots—especially when every milliamp counts in the cold.

(EVF vs LCD power differences vary by implementation, but many experienced shooters notice a practical savings using the EVF in cold conditions.)

A Simple Trick That Really Helps

One simple addition that makes a real difference is slipping a chemical hand warmer* into the same inside pocket where you keep your spare batteries. You don’t want direct contact—just shared warmth. That gentle heat helps batteries recover faster between rotations and keeps “resting” packs from dropping all the way down to ambient temperature. During prolonged −20 °C sessions, this can be the difference between a battery that comes back to life and one that stays stubbornly flat.

Practical Cold-Weather Habits

A few simple habits matter more than obsessing over exact shot counts:

Keep spare batteries inside your jacket or mid-layer, not in an exterior pack pocket.

Swap batteries before they run completely flat and warm them up before charging later.

Use the EVF instead of the rear screen when possible, and minimize review time.

Think in planned shooting bursts, not constant on-off wake cycles.

Which Sony Cameras Use the NP-FZ100?

This applies to Sony full-frame mirrorless cameras using the NP-FZ100, including:

Sony α1 and α1 II

Sony α9, α9 III

Sony α7 III and α7 IV

Sony α7R III, α7R IV, and α7R V

Sony α7S III

These cameras cover the bulk of Sony’s current battery-hungry professional bodies.

Where This Post Comes From

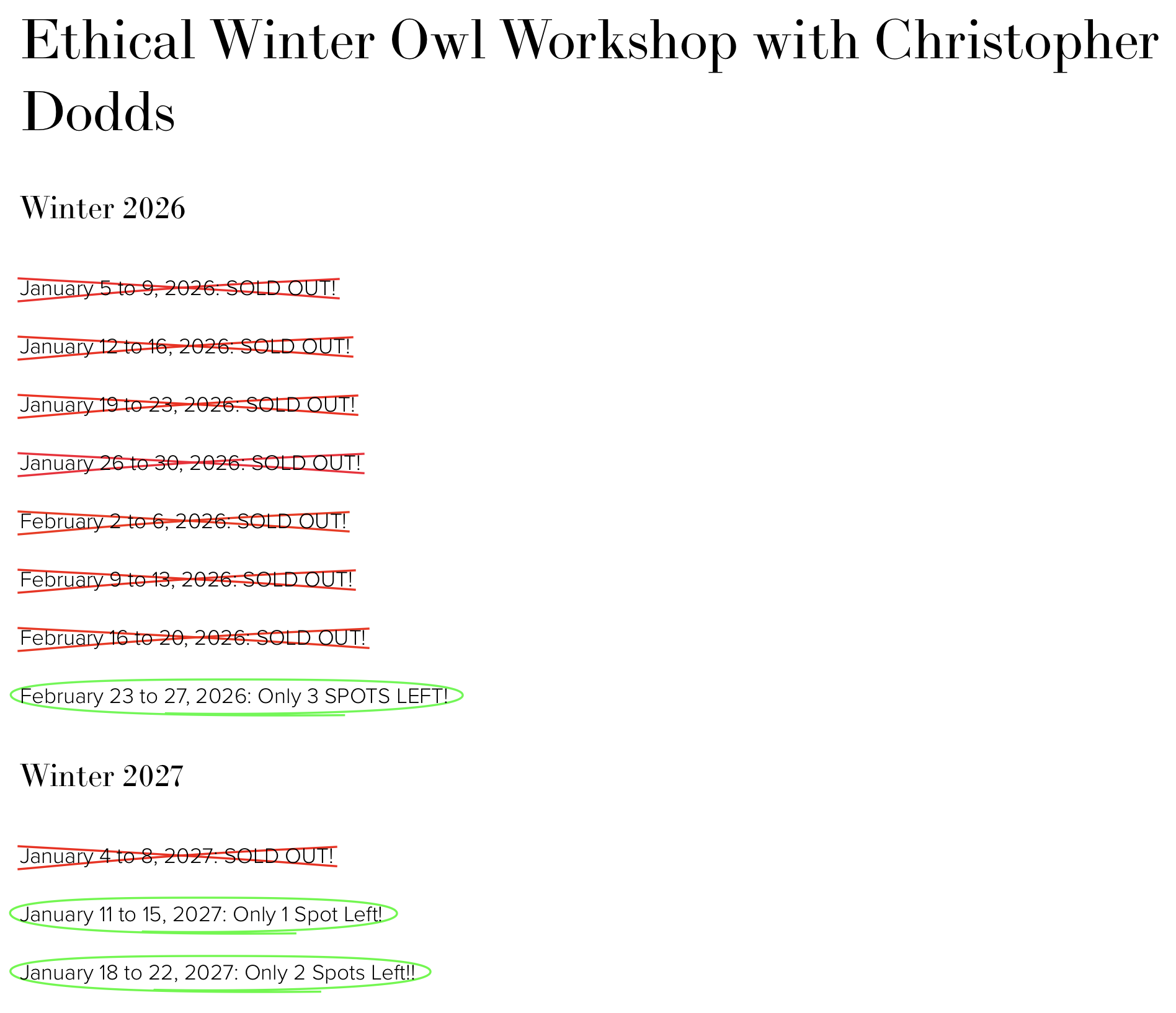

This article grew directly out of conversations during my winter owl workshops, where battery performance at −15 to −25 °C becomes a daily, practical concern—not a theoretical one.

Standing in frozen fields at dawn, rotating batteries between gloves and inside pockets, and watching cameras shut down mid-sequence inevitably leads to these discussions. Comparing notes with participants using different Sony bodies—but the same NP-FZ100—has been a great reminder that while shooting styles vary, the cold behaves very consistently.

Your Turn

Real-world experience is more valuable than any lab test.

How many frames (or minutes of video) are you typically getting from a single NP-FZ100 at around −20 °C when the camera starts warm?

Have you noticed a clear difference when the camera body itself begins the session already cold?

If you shoot with a two-battery grip, does it feel like twice as long, or more like a buffer against sudden shutdowns?

Have you tried rotating batteries with a hand warmer in the pocket—did it noticeably extend usable life for you?

Sharing honest field results from truly cold conditions helps turn winter frustration into something genuinely useful for other Sony shooters who live and work in winter.

*So-called “chemical” hand warmers are not chemical in the sense of containing hazardous substances or producing toxic reactions. They work through a controlled oxidation process (typically, iron powder reacting with oxygen) that safely releases heat. When used as intended—inside a pocket, not in direct contact with bare skin for extended periods—they are widely used, non-toxic, and safe around camera batteries and electronics. Avoid moisture and direct pressure on lithium-ion cells, but shared warmth in a pocket is both effective and well within normal field use.