Why warbler fallout makes this Canada’s best bird photography workshop location

Every spring, Point Pelee National Park becomes one of the most important bird migration stopovers in North America—and for bird photographers, it’s nothing short of magical. During my Point Pelee Spring Migration Workshop, I had the opportunity to photograph this stunning American Redstart at close range, in beautiful light, during peak migration conditions.

American Redstarts are typically fast, restless warblers—constantly flicking, darting, and disappearing into dense foliage. But spring migration changes everything.

Why spring migration is the best time to photograph American Redstarts

By the time American Redstarts reach Point Pelee, many have just completed a demanding overnight crossing of Lake Erie. This is a major physiological effort for a bird weighing only a few grams. When weather systems align—southerly winds, overnight rain, or sudden temperature drops—birds arrive low, slow, and visibly exhausted.

For bird photographers, this creates rare opportunities. Instead of racing through the canopy, American Redstarts often perch at eye level, forage methodically, and pause just long enough for carefully composed images. These conditions are exactly why spring migration at Point Pelee is so productive for photography.

Gear and approach in the field

This image was made using the Sony a9 Mark III, paired with the Sony FE 400-800mm f/6.3-8 G OSS Lens @790mm—a really portable setup that allows me to keep a respectful distance while still filling the frame with fine detail. During migration, patience and restraint matter more than speed. When birds are tired, ethical fieldcraft means letting them settle, feed, and recover while you work quietly and deliberately.

American Redstart migration facts

American Redstarts are long-distance migrants, wintering in the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America. Each spring, they travel thousands of kilometres to reach breeding territories across Canada and the northern United States. Point Pelee, as the southernmost point of mainland Canada, acts as a critical first landfall—making it one of the best places anywhere to observe and photograph them during spring migration.

When warbler fallout happens at Point Pelee

On the right mornings, Point Pelee delivers what birders and photographers dream about: warbler fallout. Dozens of species—American Redstarts, Blackburnians, Magnolias, Bay-breasted Warblers, and more—can be found feeding low, resting in open cover, and allowing intimate views that are rarely possible elsewhere.

When fallout occurs, the park feels alive. Every trail holds possibility. It’s not about chasing birds—it’s about slowing down, reading behavior, and letting moments unfold naturally.

Join my Point Pelee Bird Photography Workshop

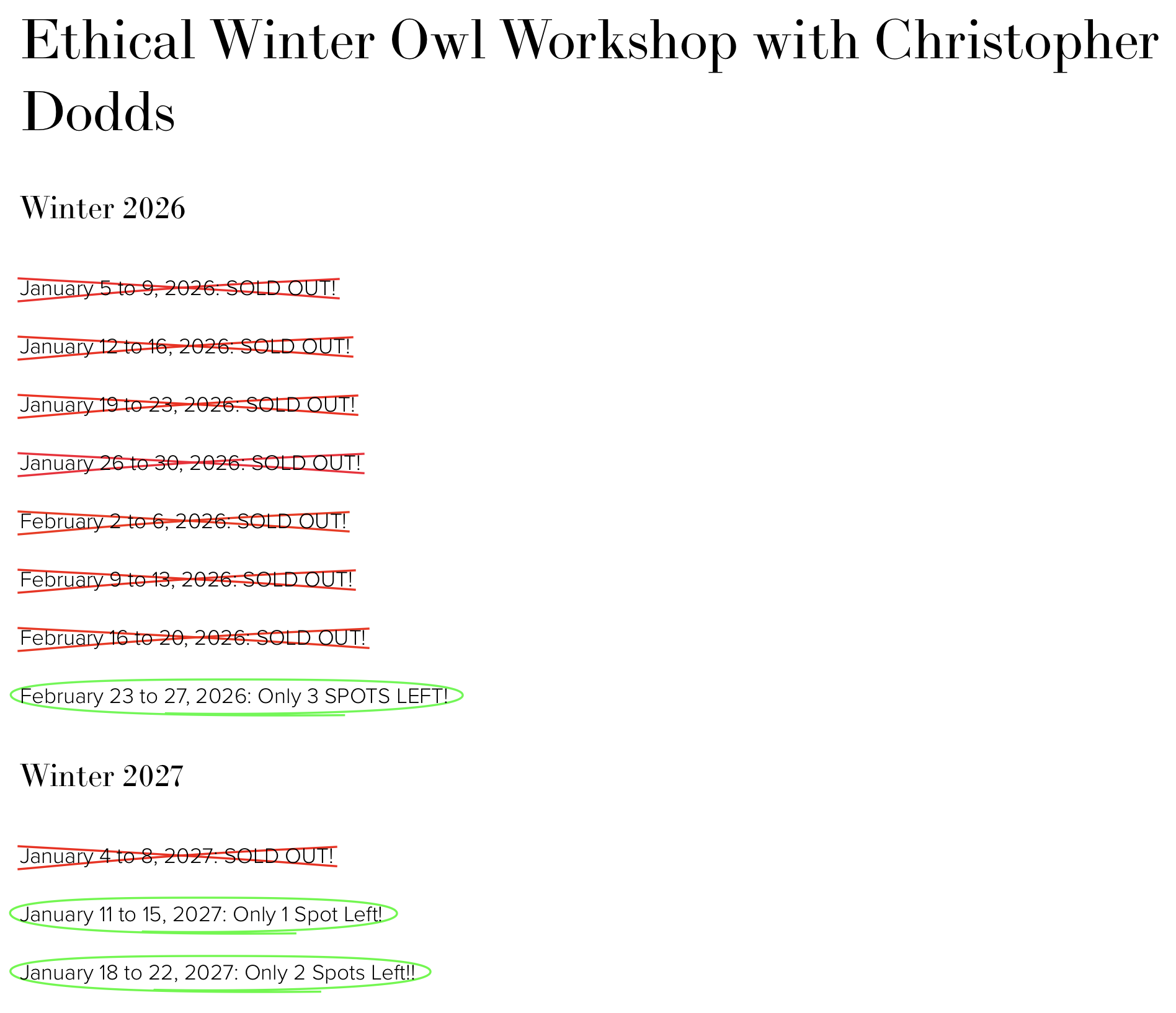

If photographing American Redstarts, experiencing warbler fallout, and immersing yourself in spring migration at Point Pelee sounds appealing, I invite you to join me for my Songbirds of Pelee Bird Photography Workshop, running May 7–11.

📸 Limited spots available.

👉 Join me at Point Pelee this May and experience one of the finest bird photography workshops in North America—right in the heart of spring migration.